| Time To Row Or Sail? |

| By John Mauldin |

Published

08/6/2012

|

Currency , Futures , Options , Stocks

|

Unrated

|

|

|

|

Time To Row Or Sail?

A few weeks ago, Ed Easterling and I updated the work we published almost ten years ago about secular bear and bull markets in chapters 5 and 6 of Bull's Eye Investing. This week I am in Maine at the annual Shadow Fed fishing trip (for those of us whose invitation to Jackson Hole keeps getting lost in the mail). Ed has graciously agreed to do another piece with me on the earnings, or business, cycle, which is different in timing than the secular stock market cycle but is part of the total warp and woof of the markets. When you combine them, you get a much clearer picture of the markets.

Earnings are a topic of great debate. At any given time, you can hear someone on TV talking about how "cheap" the market is, while the person on the next channel goes on about how expensive the market is. Today we look at the cycle of earnings, rather than a specific point in time. Let me give you a little preview. In terms of time, this earnings cycle is already longer than average, and in terms of magnitude it is projected to go to all-time highs. Which makes one want to think about whether current projections are realistic. So let's jump right in. (Note: This letter sets the Thoughts from the Frontline record for the number of charts, so it will print longer than usual, but the number of words is about average.)

But let me note that this week is the start of the 13th year of Thoughts from the Frontline. I started in August of 2000, talking about how the US would be in recession in 2001, analyzing the yield curve, which was beginning to seriously invert and which was also the signal for the recession call for 2007. I began with about 2,000 email addresses, gathered from readers of a previous print letter for another publisher and the readers of my first best-seller; and for whatever reason the list began to grow, and within a few years my entire business model changed, thanks to you, the readers and friends of this letter. The list has now grown to around 1 million of my closest friends and is posted on more websites than I ever imagined it would be. Who knew, 13 years ago, that this thing called the internet would be so cool? I am very grateful for your support.

I started Thoughts from the Frontline as a free service and hope to continue writing it for free for many years, as long are there are a few close friends who will still read my musings. My writing and thinking have evolved over the years, but I still sit down each Friday, wherever I am, and write about what I found interesting in all the reading I did the past week. I still find it exhilarating to hit the send button at the end of the process, every Friday night, and I relish the connection I feel with and the feedback I get from my readers.

And so, with an appreciative heart, here is this week's letter, as we kick off another year. And what a year it promises to be!

Time to Row, or Sail?

In April 2007, while forecasters predicted at least two more years of increases, the first "Beyond The Horizon" article stated:

"Earnings have increased at double-digit growth rates for five consecutive years – although many agree that earnings growth may be slowing, it's beyond almost everyone's foreseeable horizon that earnings might actually experience a decline."

By the end of 2007, earnings per share (EPS) for the S&P 500 declined versus 2006.

By the end of 2008, after an 80%+ decline in reported earnings, it was beyond almost everyone's horizon that reported net earnings would recover to more than $90 per share over the subsequent several years … yet this year's forecast is now $93 and next year is expected to top $103 per share.

Since the fundamental principles of the business cycle cause history to repeat itself, a decline in EPS should not be beyond your horizon!

Currently, profit margins are cyclically high, near historical highs, and already at unsustainable levels, with projected further increases over the next two years. Beware.

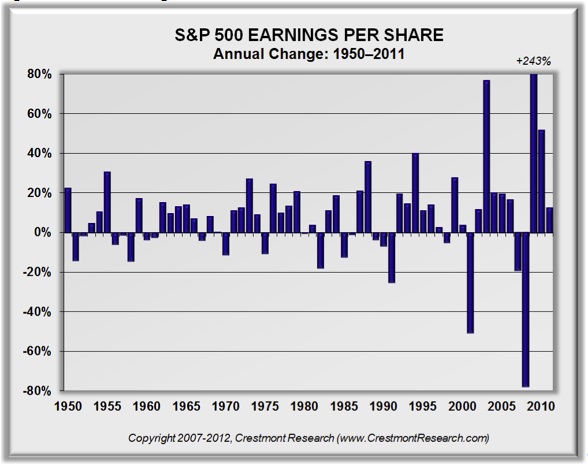

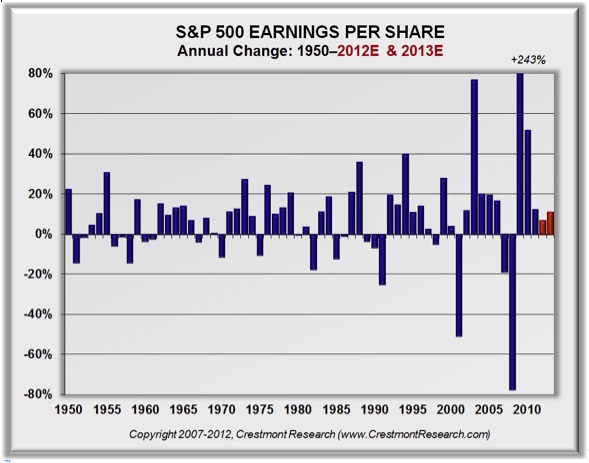

A look back at history provides insights about the earnings cycle and what is considered to be normal. Despite the statistics about average earnings growth, the business cycle drives periods of surge and stall. And the stall is generally a year or two of outright retreat, rather than smoothly slower growth. As reflected in Figure 1, earnings typically grow handsomely for three to five years, and then decline for a year or two before again growing. That's usually all that it takes to restore the balance.

Figure 1. S&P 500 Earnings Per Share Growth: 1950–2011

This choppy, irregular pattern has endured across periods of war, technological and business innovation, political issues, and other sorts of change. Yet the business cycle is not short; it does not run its course within a year. To more accurately see the trends, we can extend the period a few years to present the cycle as a multi-year average.

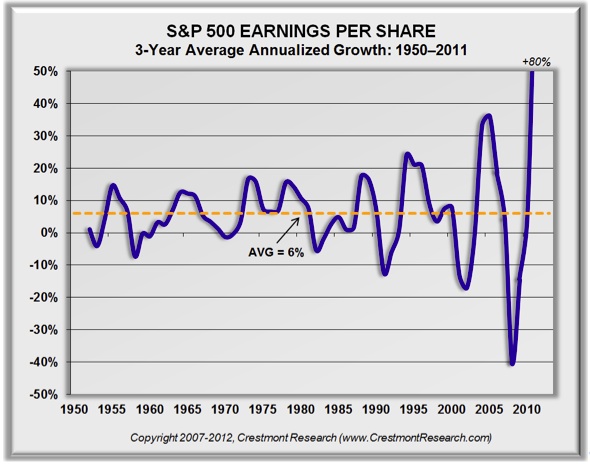

Figure 2 presents the three-year average growth rate for earnings. The cycle, while still somewhat erratic, begins to show its more cyclical nature – and the tendency for it to return to a baseline growth rate.

Figure 2. S&P 500 EPS 3-Yr. Average Growth: 1950–2011

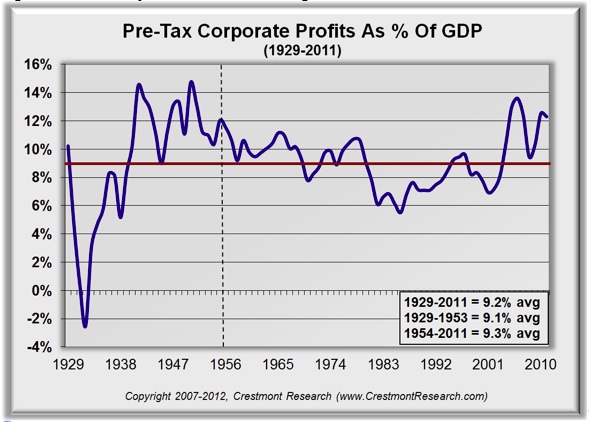

Profits not only grow and decline in dollar terms; they also change in relation to the amount of sales that it takes to generate the profits. Described in more detail, profits are the portion of sales that companies keep after all costs and expenses. When profits are compared to sales, the resulting ratio is known as the profit margin. As economists will acknowledge, the business cycle tends to push profit margins around a base level. When the sales of all companies are consolidated together, the result is essentially gross domestic product (GDP). Therefore, the aggregate profits of all companies can be compared to GDP, as a measure of profit margins and relative profitability.

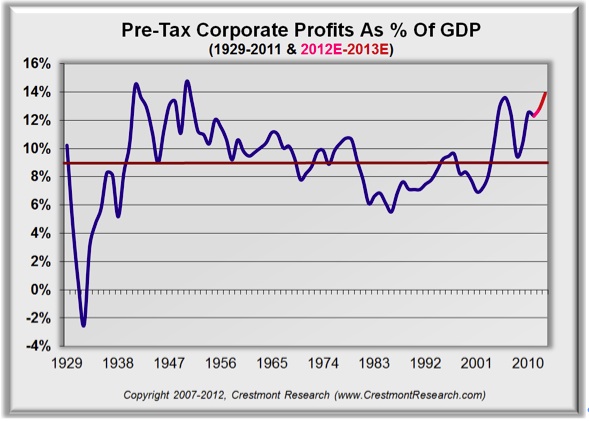

Figure 3 presents the profit margin relationship since 1929, when the data was first readily available. The relationship has not been smooth, yet it has been fairly consistent. During the Great Depression, profit margins were low and negative. That underperforming period was followed by an extended era of above-average profit margins. The average for the entire period of over eighty years from 1929 to 2011 is approximately 9%. Interestingly, the average for the first twenty-five years (1929-1953), with its extremes, also averages almost 9%.

The extremes in both directions during the early part of the last century counterbalanced each other, as would have been expected in order to achieve the "normal" average. Following 1953, the average has also been near 9%; yet with less-extreme cycles. (Note: 1953 was used as the cutoff year to reflect a twenty-five year period and to encompass all of the more extreme years during the first half of the past century.)

Figure 3. Pre-Tax Corporate Profits as a Percentage of GDP: 1929–2011

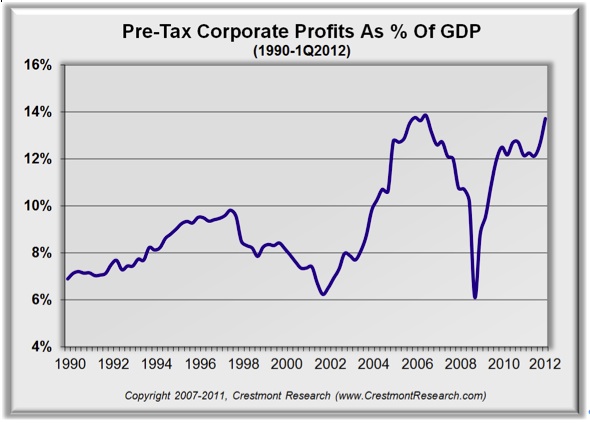

Today, as highlighted in Figure 4, using quarterly data, profit margins have moved well above the historical baseline near 9% and are vulnerable to being restored again toward the average. It does not necessarily have to happen immediately, as these cycles are slow-moving. It is likely, however, to be forthcoming.

Figure 4. Pre-Tax Corporate Profits as a Percentage of GDP: Quarterly 1990–1Q2012

Analyst forecasts remain optimistic despite recent indications of weakness. As of July 31, the forecast by Standard & Poor's for this year and next year reflects continued earnings gains – to more than $103 per share. Figure 5 adds the percentage increases for the next two years to Figure 1. This puts into perspective the notion that we're supposedly on track for one of the longest runs ever of earnings increases.

Figure 5. The Analysts' Forecast: S&P Outlook – Percentages

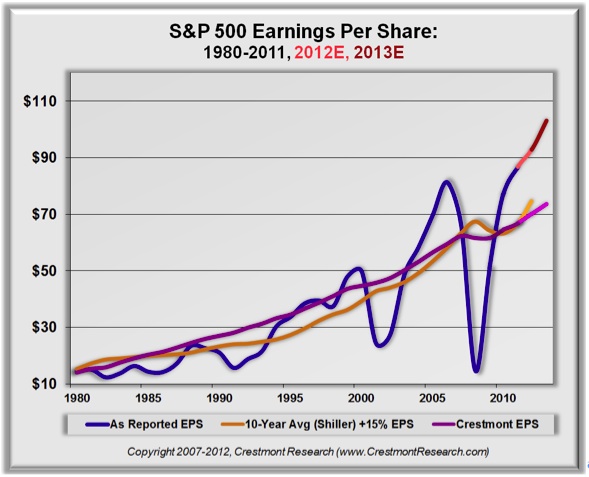

How can we put the level of earnings into perspective? There are two methods to normalize earnings described in Ed's most recent book, Probable Outcomes. The first is a method popularized by Robert Shiller at Yale and the other is a methodology used by Crestmont Research. The blue line in Figure 6 is actual reported EPS; the red line extension is S&P's forecast. The orange and purple lines are baseline normalized EPS using Crestmont's & Shiller's methodologies.

As reflected in Figure 6, both methods reflect similar results over time. Most noteworthy in this chart is the high degree of variability for reported earnings in relation to the normalized measures. This chart is probably one of the the best ones by which to appreciate the high degree of fluctuation for reported earnings across business cycles.

Figure 6. The Analysts' Forecast: S&P Outlook – Dollars

Note in Figure 6 that the current and forecast levels of earnings are becoming quite elevated above the normalized growth baseline. This is another indication that profit margins have become extreme. But how extreme?

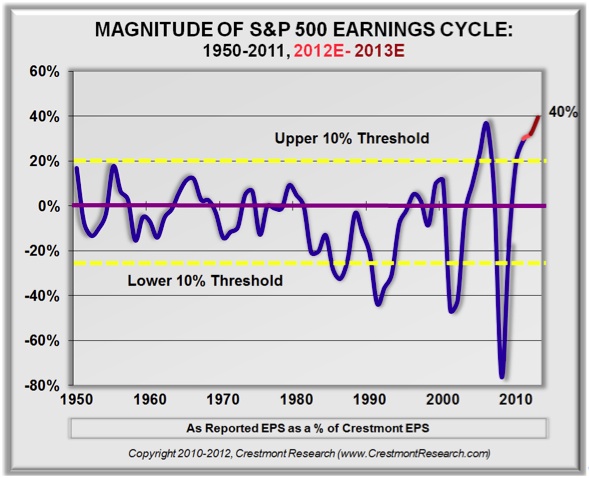

Figure 7 presents the percentage difference between actual and forecast reported earnings compared to Crestmont's measure of normalized earnings. This enables us to see the relative difference as a percentage. That makes the chart comparable over longer periods of time when the actual dollar level of earnings is increasing.

Two yellow bands are included on the chart to mark the middle 80% and outlying 10% of the points on each side of the middle. Most of all, the chart highlights just how far beyond the normal range we have currently gone and are forecast to go. By the end of next year, we're expected to be 40% above the normalized level of earnings. And since the trend tends to overshoot the baseline, the potential decline in reported earnings will certainly surprise a lot of analysts (but no longer will it surprise our readers!). Therefore, the current position in the earnings cycle is extended not only in terms of duration, but also in magnitude.

Figure 7. Magnitude of EPS Over/Under Baseline Trend

Although the two methods for presenting profit margins in the business cycle are not directly comparable, we can overlay the information for some level of additional perspective. There are few well-followed forecasts for national profit margins. Figure 8 depicts national corporate profits, with a pro forma extension using the S&P 500 forecast for reported earnings growth in 2012 and 2013.

The press is now filled with stories about record profit margins. It's clear that the current record goes back a long way. This, of course, means that there's quite a long ways to fall, too.

Figure 8. Comparable Profit Margin Analysis

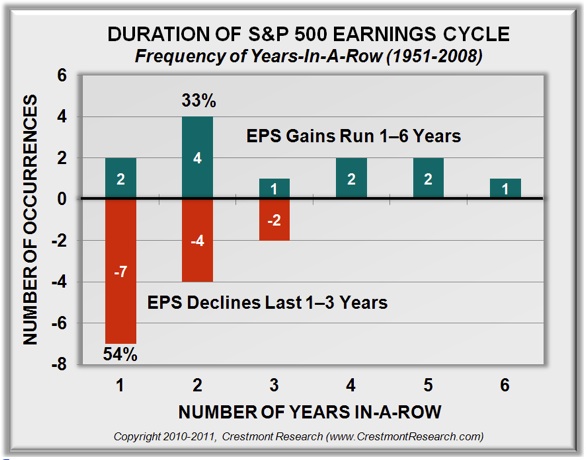

What about the duration of earnings cycles? Past EPS cycles have lasted one to six years. Over the past six decades, there have been twelve up-cycles. Six lasted one or two years (last year, 2011, was year three of the current cycle). We're now in the second half of the game. As each upcoming year passes with an increase in EPS, the likelihood rises for the next decline in EPS … and potentially the stock market.

Conclusion #1: Reported earnings, based on history, should be expected to decline over the next two years (or they are increasingly likely to disappoint current expectations). That will put pressure on the stock market. If history is a guide, and if the blue line in Figure 8 only slightly retreats below the historical baseline, the implication is a decline in reported EPS of almost 40%! While growth could continue (as it has done in the past), it is clear that this cycle is getting a little weathered. And note that almost every downturn came as a surprise to the markets. Any analyst suggesting a downturn is labeled doom and gloom (as we can attest).

Conclusion #2: The measures of P/E that are based upon reported EPS are currently distorted by the business cycle. Whereas current reports have the market's forward P/E near 13, a more rational measure for P/E based upon normalized baseline EPS is close to 20. P/E is not below average and is not ready to propel the market upward; it is well above average.

Figure 9 highlights the duration of EPS cycles. The chart will not include the current cycle until it is complete. Of the twelve up-cycles, half of them ended after one or two years of rising earnings. None of them exceeded six years, and only one went that long. Since 2011 was the third year of earnings gains for the current cycle, the likelihood of a decline is increasing. If a decline happens to not occur during the coming two years, then we'll make history.

When declines have occurred in the past, they most often lasted only one year. But just under half of the time, the decline extended for two or three years. Given how far this cycle has extended in magnitude, it's unclear whether the next decline will be a brisk annual event or a torturous few years.

Figure 9. Duration of EPS Cycles

A Few Implications

The stock market and earnings analysts do not expect a decline in EPS over the next few years. The forecasts too often anchor on the recent past and extrapolate (in a burst of hope) current trends well into the future.

A broader view of history tells a different story. It is a story of a frequently erratic earnings cycle. The current cycle is now extended not only in duration but also in magnitude. It's hard to deny that EPS is vulnerable to decline over the next few years.

When the decline in earnings occurs, it will not be minimal. The decline to the historical average would be 30% to 40%. These cycles, however, rarely stop at average. More often, they move well above and below the long-term trend line.

We've all seen that the stock market reacts to surprises quite negatively. There is no reason why investors should walk blindly into this storm. "Who knew?" will not a reasonable excuse.

Active portfolio management can position portfolios to participate in further upside until the downturn occurs, then it can provide protection from the full brunt of the ensuing losses.

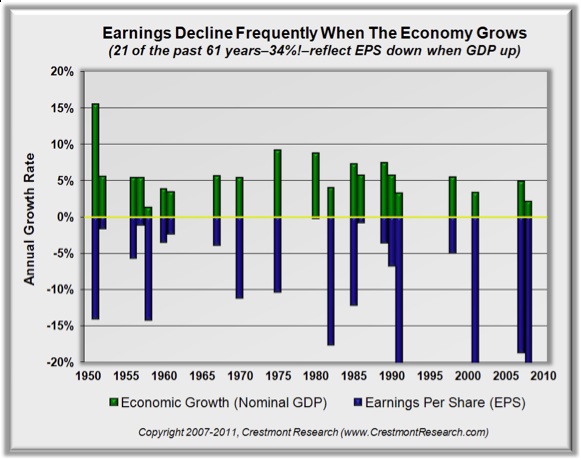

Some people will read the outlook for a decline in earnings to portend a recession, but earnings declines happen much more frequently than recessions. The business cycle is distinct from the economic cycle. As reflected in Figure 10, over one-third of the past 61 years have seen EPS declines despite growth in the economy. So, don't be surprised that EPS might decline in spite of continued economic growth.

Figure 10. EPS Downturns Without Recessions

A weak economy, however, adds to the pressure on earnings. The typical vulnerability at this level in the cycle is accentuated by the external forces of the economy. That makes the risks particularly worrisome.

It's Time to Think About Absolute Returns

As described in chapter 10 of Probable Outcomes and chapters 9 and 10 of Unexpected Returns, the goal is to use absolute return-oriented "rowing" investments rather than more passive relative return "sailing" strategies. Although the stock market will provide shorter-term periods of solid returns over the next decade, it will also have offsetting periods of declines. Unlike secular bull markets, where the upswings far outweigh the downdrafts, the current environment is set for a much more modest (and likely disappointing) result. Rather than acquiesce to the mediocre returns on the horizon, investors can take action and develop their portfolios to profit regardless of the overall market direction. Although market timing may be an option for some, it is generally not a good option for most investors.

Conclusions About the Earnings Cycle

The business cycle has endured for well more than a century. It generally delivers two to five years of above-average EPS growth before experiencing a year or two of pullback. We have had a dramatic run over the past two years, and the forecast for the next two years now positions profits well above their historical relationship to the economy.

Several factors now indicate that a period of EPS decline may be upon us. It does not necessarily portend a decline in the market, although that vulnerability clearly exists. Beware nonetheless! For investors, this means that portfolios should be positioned through diversification and active risk and return management.

As an analogy, winter is not a time for gardeners to hibernate; rather it's a time for different crops and techniques than you employ in spring or summer. And let's be certain about this: there will be a new spring, and I will turn bullish – probably too soon! – as we begin to see signs of a thaw in the markets. But for now, investors have many tools available that let them actively "row" and invest like institutions, thereby achieving relatively consistent returns with a lot less disappointment risk.

In the meantime, I still look for alternatives to a buy and hold strategy for the general stock market. That strategy is an exercise in futility in a secular bear (but will become a thing of beauty when the cycle turns). In today's world there are lots of options for the serious investor and student of the market. Rather than trying to beat the market, my benchmark today is a T-bill. How much can we make over the returns of a short-term treasury, with an appropriate plan for safety and liquidity? Bonds, real estate, income-oriented investments, arbitrage, alternative funds, and their kin are all options. I find the obsessive focus with the stock market a real oddity, somewhat akin to giving a full company of soldiers only one gun, or bringing a knife to a gunfight. It's a strategy, but not a winning one.

As I close this letter, let me refer you to a new paper by my partners at Altegris Investments, called "The Case for Liquid Alternatives," which you can find at www.altegris.com. Just click on your category of investor and you will find that paper and others on alternative invetments.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|

|